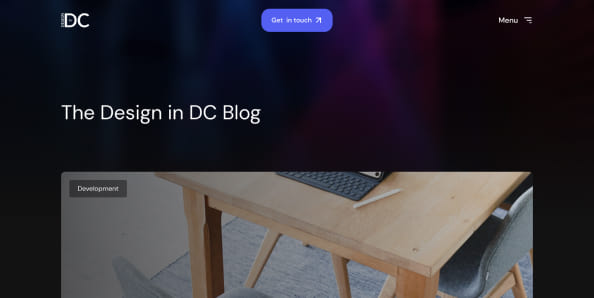

The Story Behind the Design of Washington, D.C.

Our name, Design in DC, says it all. At the core of our services—ranging from SEO to re-branding to website creation—is a reverence for design. And, of course, we’re based in the nation’s capital, which also happens to be a premiere tourist destination. But while we’ve discussed many design-related subjects on this blog, one we haven’t yet covered is, “Who designed Washington, D.C.?”

Turns out, it’s a complicated, yet highly intriguing and inspiring, story which involves a Frenchman, a Renaissance man, a few famous historical figures and, as expected in D.C., lots of politics. It also features something we at Design in DC know a lot about—teamwork.

Washington, D.C., Here and Now

When most people think of D.C., they think, seat of government. The U.S. Capitol, Congress, the Supreme Court, the White House. They also think of protests and celebrations, like the Presidential Inauguration and the July 4th fireworks lighting up the city’s skies.

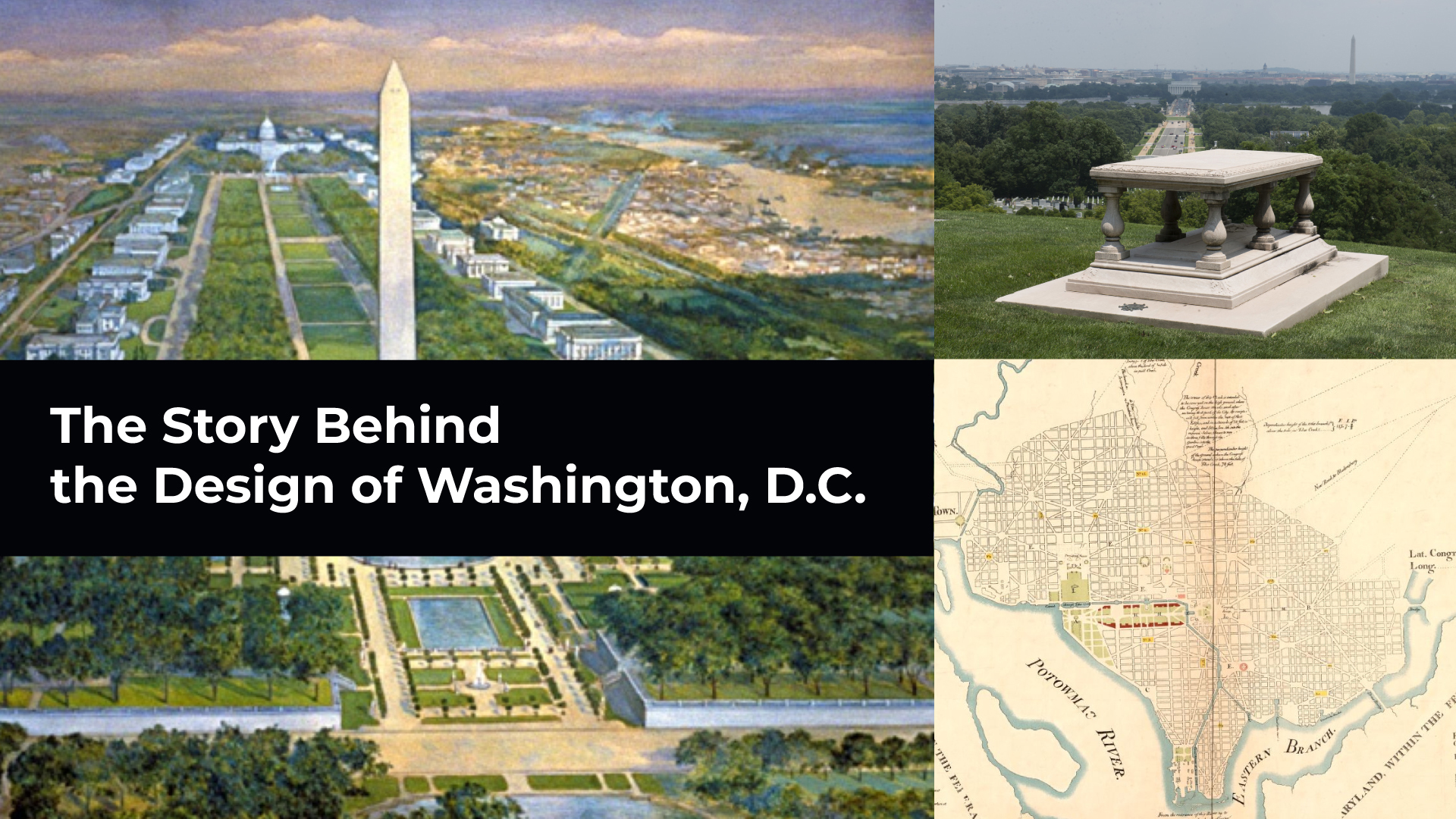

At the center of it all is the National Mall, the two-mile expanse of land stretching from the U.S. Capitol to the Lincoln Memorial, with the Washington Monument, the city’s tallest structure, in between. And on the sidelines are all those wonderful (and free) Smithsonian museums—Natural History, Air and Space, the Hirshhorn, to name a few.

What many don’t focus on are D.C.’s neighborhoods, the multi-block communities where people live, work, play and thrive, each centered around a park, some of its streets named after states. The most famous is the one that runs between the U.S. Capitol and the White House, Pennsylvania Avenue.

More than 200 years ago, the 61-square-mile chunk of land wasn’t a city at all. It was a mix of farms, forests and hills divided between Maryland and Virginia. But because of its location—wedged between two major rivers and a northern and southern state—it was considered an ideal location for a then-new national government. Thanks to the Residence Act of 1790, that’s exactly what it became.

And, then, the hard part—designing the district. Just so happens that George Washington, the country’s first president, knew just the guy.

Meet Pierre L’Enfant, the Primary Designer of Washington, D.C.

Born in Paris in 1754, Pierre Charles L’Enfant was the son of a painter and professor at an arts academy, where Pierre studied in his late teens and early twenties. In 1776, with America’s Revolutionary War underway, Pierre volunteered to join the rebel cause, then spent the next several years as an Officer in the Army Corp of Engineers, including a stint with Washington at Valley Forge.

By the time the war was over, he’d completed a number of high-profile design projects, which won him favor with the likes of Washington and Thomas Jefferson and landed him a job in a New York City architectural firm. He not only designed coins, medals, furniture and houses, but a church altar as well. And in 1788, he was commissioned to redesign NYC’s Federal Hall, which, at the time, housed the national government.

When it came to politics, L’Enfant was no novice. Knowing a movement was afoot to establish a future federal city, he put a bug in Washington’s ear—by writing a letter to him in 1789, offering his services. It worked. So, in 1791, when it was time to launch the D.C. design project, L’Enfant led the way, coming up with a plan that would impress many but also prove his undoing.

A Bold, Egalitarian Design

When L’Enfant arrived in Georgetown in March of 1791 to conduct a survey of the land, he had a vast knowledge of European cities, including his hometown of Paris, as well as a passion for the democratic ideals of his newly adopted country. He’d later write a letter to Jefferson saying he wanted to turn the “wilderness” into a city worthy of the newly established empire.

The plan was bolder than anyone imagined. Atop a conventional grid of streets, he overlaid a network of broad, diagonal axes featuring wide boulevards, public squares and spaces reserved for government buildings. Included was a wide swath of open space, which would later become the National Mall.

At the center of it all, however, would not be a palace, as in European cities, but the headquarters of those elected to Congress—the U.S. Capitol. And it would sit on a hill overlooking the entire city, including, just down Pennsylvania Ave., the president’s residence, later to be known as the White House.

“The entire city was built around the idea that every citizen was equally important,” L’Enfant biographer Scott Berg told Smithsonian Magazine. “The Mall was designed as open to all comers, which would have been unheard of in France. It’s a very sort of egalitarian idea.”

Enter Benjamin Banneker, Exit L’Enfant

Part of the design project involved another couple gents, residents of Maryland. One, an engineer named Andrew Ellicott, was in charge of surveying, or mapping out, the land in great detail. The other, Benjamin Banneker, was his assistant and a free Black man with a background like no other.

Maryland was a slave state in the 18th century, but Banneker, born in 1731, was the son of a former slave who’d been given his freedom and a woman of mixed race. So he entered the world free and grew up on the family’s 100-acre farm. The literacy rate in the region was low, but Banneker, with his innate thirst for knowledge, gobbled up every bit of information he could in school and via books.

As an adult, he was a true Renaissance man. Among other feats, he hand-carved a working wooden clock, built an irrigation system for the farm, taught himself astronomy, ran a tobacco business and authored several popular almanacs.

He also made friends with the Ellicott family, entrepreneurs and owners of a gristmill, one of whom, Andrew, was hired by L’Enfant to survey the land for the new seat of government. Aware of his astronomical skills, Ellicott hired Banneker to map out the district’s boundaries.

But L’Enfant, by this time, was running into difficulties. Even though Washington had appointed three commissioners to oversee the D.C. project, L’Enfant thought himself answerable to the president only. So when disputes arose over the purchase of properties to clear the land, L’Enfant plowed ahead, at one point ordering, without permission, the demolition of a landowner’s house to ensure his plan was fully realized.

The commissioners complained, and Jefferson, secretary of state at the time, stepped in to help make peace. But L’Enfant wouldn’t budge, so Washington, feeling he had no choice, fired him. A very unhappy L’Enfant left the project, reportedly taking his plan with him.

“Reportedly” because the next part of this story is the subject of dispute. Some claim that Ellicott saved copies of L’Enfant’s plan, while others claim it was Banneker, with his insatiable curiosity and natural talents, who was able to sketch out the plan completely from memory.

Either way, a version of L’Enfant’s plan was used to launch construction of the district project at the start of the 19th century. But the D.C. we know today would be put on hold for more than 100 years.

D.C. is Redesigned, L’Enfant’s Reputation Restored

Here at Design in DC, it takes us anywhere from six to 12 weeks, working closely with a partner (aka client), to design and either refurbish or build a brand- and SEO-ready website. But building a capital city from scratch—as with Rome, it takes more than a day.

The same was true in D.C.’s case. For many reasons—including L’Enfant’s dismissal, the politics of real estate and a Civil War—the fully-realized D.C. took time to roll out. By 1900, the city was still something of a backwater, populated by farms and cattle and a “mall” which was just a collection of parks. It was an embarrassment for many, not the symbol of a great nation.

So a Congressional commission—composed of legislators, architects and planners—was formed with the idea of using L’Enfant’s original plan as a guide. “The McMillan Plan,” named for the commission’s chairman, Sen. James McMillan, essentially realized L’Enfant’s vision and, over the next few decades, resulted in the construction of the National Mall, museums, monuments and government buildings standing today.

L’Enfant, while still alive, didn’t fare as well as his plan. While he went on to oversee several significant projects, including the design of Paterson, New Jersey, he suffered financial hardships and died poor, at age 71, in 1825. Afterwards, he was buried on the farm of a friend.

But in 1909, with his reputation restored, his body was exhumed and moved to a place reserved for national heroes, Arlington National Cemetery, just across the Potomac from Washington, D.C. His gravesite, marked by a monument, lies on a hill overlooking the city he’d once envisioned.

The Design of Washington, D.C.’s Legacy

We learned a few things digging into the question of who designed D.C. One is that city planning is a monster of a design job, which, if done right, starts with a bold vision. But it’s also not a one-person job. That vision needs to be planned and executed by a team of experts working in harmony.

While Design in DC’s jobs aren’t as big as L’Enfant’s was, they are substantial, and we rely on teamwork. And one vital member of our team is the client, whom we prefer to call “partner.”

We invite you to take a look at our other blog posts covering the subject of design. And, if you’re interested, we encourage you to reach out and start a discussion about how we can help your business or organization redesign your brand.

Meantime, our hats are off to Pierre L’Enfant—for inspiring us and paving the way for a city as unique as his vision.